Local Authorities rely on private sector advisers to structure, broker, advise on and manage their financial affairs. These firms, known as Treasury Management Advisers (TMA) not only charge high fees, but act with significant conflicts of interest, whilst encouraging Council Treasurers to behave like short term, profit driven, investment bankers.

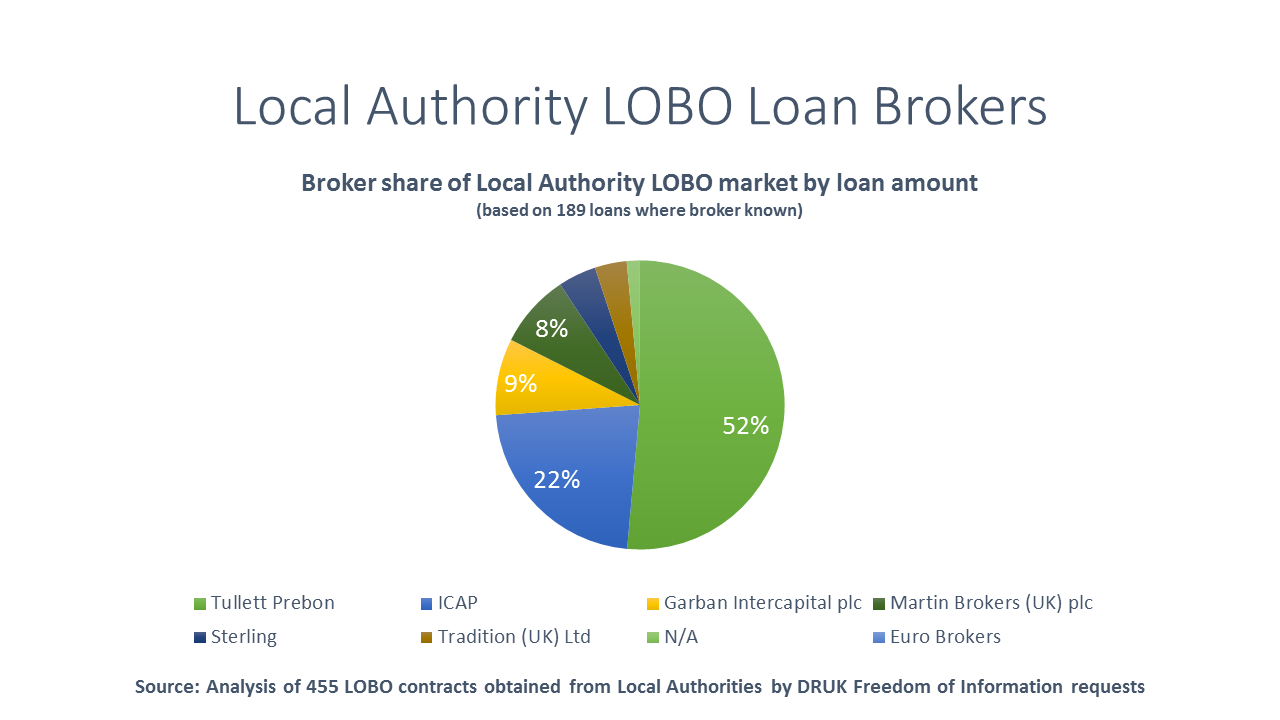

When Councils take out a LOBO loan they do not generally deal directly with the banks, but through brokers, such as ICAP and Tullet Prebon, who charge substantial fees to both the council and the bank to structure the deals. Fees can reach as high as £75,000, alarmingly higher than the corresponding PWLB flat rate fee of £75. Brokerage fees on LOBOs quickly add up to significant sums of public money – for example £1m at Kent County Council.

Brokers receive commission payments from the banks they deal with, in the form of a percentage (up to 1%) of the loan amount they manage to secure. 1

Once funds are obtained, Council may invest the funds for up to three years before committing them to the relevant capital project for which they were borrowed. During this time Councils need to put the funds somewhere until they are called upon, so they invest with financial institutions to maximise returns.

With LOBO loans, Local Authorities are given the opportunity to borrow cheaply in the short-term, using low short-term teaser rates, to re-invest this money until needed for three years in high interest/ high risk investments, such as in Iceland in 2008.

Councils, in order of importance, need to ensure that their investments provide:

- security (i.e. investments are safe, having a strong AAA credit rating);

- that they have sufficient liquidity (or ease of accessibility to funds when needed);

- that they provide acceptable returns, known as yield.

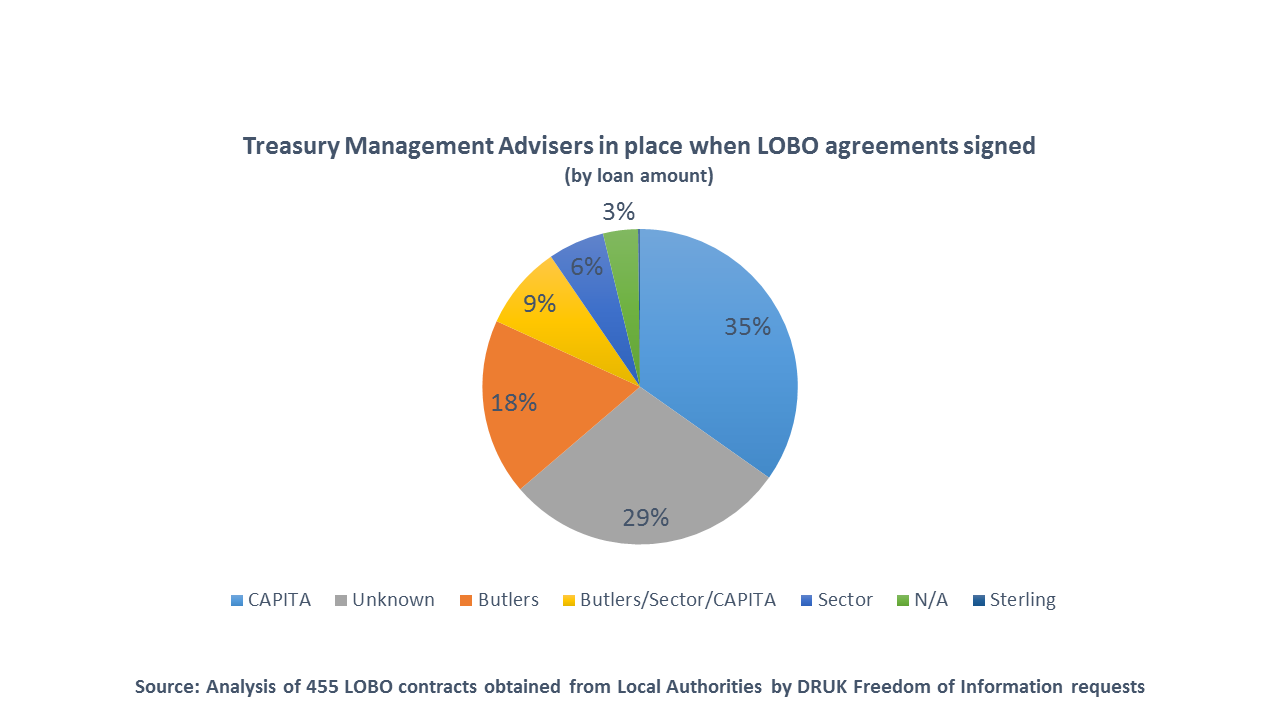

As the average councillor is not a financial expert, to support financial decisions, regarding borrowing and investing, Councils pay for ‘independent’ advice from the financial sector, through firms known as Treasury Management Advisers (TMA), such as Butlers and CAPITA.

The role of TMA companies was criticised following the Icelandic banking crisis, when local authorities lost £1 billion on deposit with Icelandic banks when they crashed in 2008. 2 The main TMA firms then were, with a combined 84% market share, Butlers, a subsidiary of ICAP, and Sector, a subsidiary of CAPITA. 3

At the time of the Icelandic scandal, concerns were not only raised regarding the Council losses, but also with regards to clear conflicts of interest between subsidiaries and parent financial companies. While one part of the organisation (Butlers) was providing financial advice on Council investment, another part of the same organisation (ICAP) was earning brokerage commission on trade referred to it by the advisor, earning substantial profits on both sides of the trade.

In the case of LOBO loans, Butlers which advised councils to take out the loans was a trading division of ICAP plc which profited from the loans. CAPITA meanwhile received an undeclared income stream by referring local authorities clients to trade via Tullet Prebon.

Both scenarios call into question the independence of advice, upon which local authorities relied and CAPITA and Butlers profited. In both cases, advice regarding LOBOs may constitute false misrepresentation – a situation worsened by the clear profit motive for advisers to refer clients to the banks, not the PWLB.

With LOBO loans advisors and brokers have secured huge profits by incentivising Council Treasurers to behave like short term, profit driven, investment bankers.

An analysis of 126 LOBO loan transactions where the broker fee is known (obtained via DRUK Freedom of Information requests to Local Authorities) provides an estimate of the fees earned by brokers on loans which are still outstanding: £29.8m. This figure doesn’t include loans which have already been paid off.

Given the high brokerage commissions paid to brokers (and in some cases advisors) when Local Authorities borrow from banks, it is hard to believe that LOBO loans are recommended with the interests of taxpayers in mind.