Perform a Google search for ‘Weymouth LOBO’ and the first result will probably be a story about a builder named Martin Lobo who had to pay a £5k fine for misleading the proprietors of a Weymouth guest house. The couple paid Mr Lobo to raise the roof of their property but the work he did turned out to be of such poor quality it cost them £30,000 to put right.

Builder from hell? Perhaps. But Mr Lobo has a namesake in Dorset that represents an equally misleading proposition and which could end up costing the taxpayers of Weymouth and Portland Borough Council a great deal more than £30k.

LOBO loans and the interest rate trap

If you’ve been following Debt Resistance UK recently then LOBO loans will need no introduction.

If you haven’t, ‘Lobo’ is Spanish for ‘wolf’ but in this context LOBO stands for Lender Option Borrower Option – a kind of loan offered by banks which has embedded derivatives. Local Authorities in the UK have borrowed upwards of £11bn in the form of LOBO loans over the past couple of decades.

The word ‘derivatives’ in that last paragraph probably started alarm bells ringing for you, and not without reason. Yes, we’re talking about the same kind of exotic financial instruments that brought the global financial system to its knees in 2007-08 and the fallout of which is still being felt today in the form of low employment, stagnant wages, deflation and austerity.

Collateralised debt obligations and mortgage-backed securities managed to compound risk in the financial system while giving the appearance that risk was being mitigated. In a similar way LOBO loans may well be exposing UK local authorities to huge risks while masquerading as a good deal for taxpayers.

The particular derivatives embedded in a LOBO loan vary from contract to contract but here’s what they all have in common:

- they allow the lender (the bank) to increase the interest rate payable on the loan at fixed times (e.g. once every six months)

- they ‘allow’ the borrower (the local authority) to react to the lender raising the interest rate by paying the loan off in full

If your gut instinct is that this sounds like a rather bad deal for the local authority then your gut is probably functioning correctly. After all, the ‘options’ described are really only options for the bank – if the lender suddenly jacked up the interest rate on a loan to way above the market rate then the local authority would be left with very little option but to repay the loan.

So why do councils take out these loans in the first place? Why wouldn’t they instead borrow money from central government, via the Public Works Loan Board, at a rate that is pegged to the cost of government borrowing?

The financialisation of local government

The Local Government Act 2003 changed the way that local authorities finance themselves. Legally bound to run balanced budgets (i.e. no deficits), local authorities in the UK have to borrow money to finance large capital projects like schools and hospitals – either from central government (via the PWLB), private companies (e.g banks) or other local authorities.

In the past, a local authority needed permission from central government to take out any kind of loan but when the above act came into law on April 1st 2004 they were no longer subject to those rules. Instead, councils were to follow a Prudential Code to ensure their borrowing was prudent. (Available from the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy for just £125.)

While this putatively gave local authorities the freedom to manage their own affairs – they were now free to go to the money markets at their own discretion – it also arguably made them subject to the same kind of stat-juking short termism we’ve seen from companies like GM, Northern Rock and Kaupthing. Now that they were responsible for the numbers the pressure was to make them look as good as possible over the short term – keeping central government and the voters happy – regardless of the long term implications.

That’s assuming they were even capable of working out the long term implications. Financial whizz-kiddery is a whole lot rarer in the offices of local councils than in the halls of central government.

Access to the marketplace; the need to get the best deal possible for the short-term; financial naivete: to city brokers local authorities were coming more and more to look like fat lambs awaiting the slaughter. What was needed was a wolf in sheep’s clothing to send into the sheepfold. Enter LOBOs.

Marketing a time-bomb

Local authorities know better than to go straight to a bank when looking to arrange a loan. Instead they use intermediaries, brokers with in-depth knowledge of the markets, to arrange the loans for them in the same way that a homebuyer would use a mortgage broker. The problem with this arrangement is that the brokers earn commission from the lender whenever they arrange a loan. And LOBO loans tend to pay out much higher commission than other kinds of deals.

The race was on. Prior to the financial crisis of 2007-08 LOBO loans were marketed to Local Authorities as hedges against interest rate rises – they provided a fixed rate of borrowing over a fixed period and nullified the risk of interest rate rises. Of course, once the global crisis hit rates soon plummeted to near-zero, rendering the LOBO deals much more expensive than borrowing from the PWLB.

After the financial crisis, in the new low-rate environment, LOBOs were instead marketed with low introductory ‘teaser’ rates which beat the PWLB rate (which was raised by George Osborne in 2010 by one whole percentage point). Of course, with Bank of England rates at 0.5% it costs a bank very little to offer an introductory loan rate low enough to sucker local authorities into forgetting about the future. That’s how local authorities like Brent have ended up paying well over the PWLB loan rate on a LOBO from RBS – a deal which they’re locked into until interest rates change.

Living on borrowed time

We don’t have access to the details for most of the LOBO loans – we’re currently sending FOI requests to over 500 local authorities in an attempt to obtain the contracts and price them. Some, like Kent, have been very helpful. Others, like Newham, haven’t.

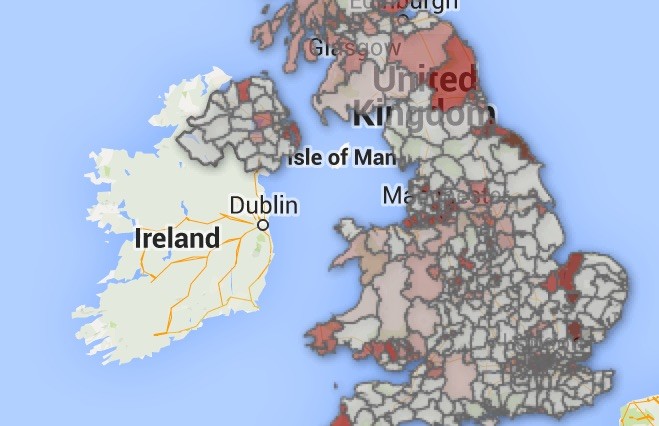

We do though have access to the Local Authority borrowing and investment figures from the Department for Communities and Local Government which helped us put together the following heatmap. The darker the local authority appears in the map the higher the percentage of that local authorities’ long-term financing comes via bank (i.e. LOBO) loans.

(NB: There are lots of local authorities that aren’t included in this heatmap – county councils, fire, police and transit authorities etc – which are also large LOBO borrowers.)

There are five local authorities whose only source of long term borrowing is LOBO loans:

- Weymouth & Portland

- Hyndburn

- Forest Heath

- Braintree

- Scarborough

We can see from looking at the accounts for each of these local authorities that they’re currently paying an effective interest rate of between 4% and 5% on their LOBO loan balances – for now. But what happens if the lenders decide to call in the loans? Not an unthinkable prospect in another credit-crunch type scenario.

In that eventuality Weymouth & Portland would find itself having to refinance £27million worth of loans. Sound do-able? What if I tell you that Weymouth & Portland Borough Council’s entire budget for 2014-15 is just £9.4m? Sound do-able now?

What about in Ashfield in Nottinghamshire where £34m of LOBO loans mean that the council would have a whole in its finances twice the size of its annual expenditure?

Or in Woking, where LOBO borrowing of £30m is the equivalent of 170% of the council budget?

You can find plenty more examples in the map of councils whose finances are looking very vulnerable in the face of interest rate rises or tighter borrowing conditions. Fans of neoliberal economic policy won’t be surprised to see clusters of red around some of the most deprived areas of the UK, further evidence that financialisation and inequality go hand in hand. Crises mean cuts; cuts mean failing public services; failing public services mean privatisation.

True to form, central government doesn’t seem too concerned by this looming local authority financial crisis. In fact, quite the opposite. The Audit Commission, responsible for ‘protecting the public purse’ by auditing the books of public bodies in England, is being shut down on the 31st of this month.

Which leaves no one guarding the sheep but the wolves.