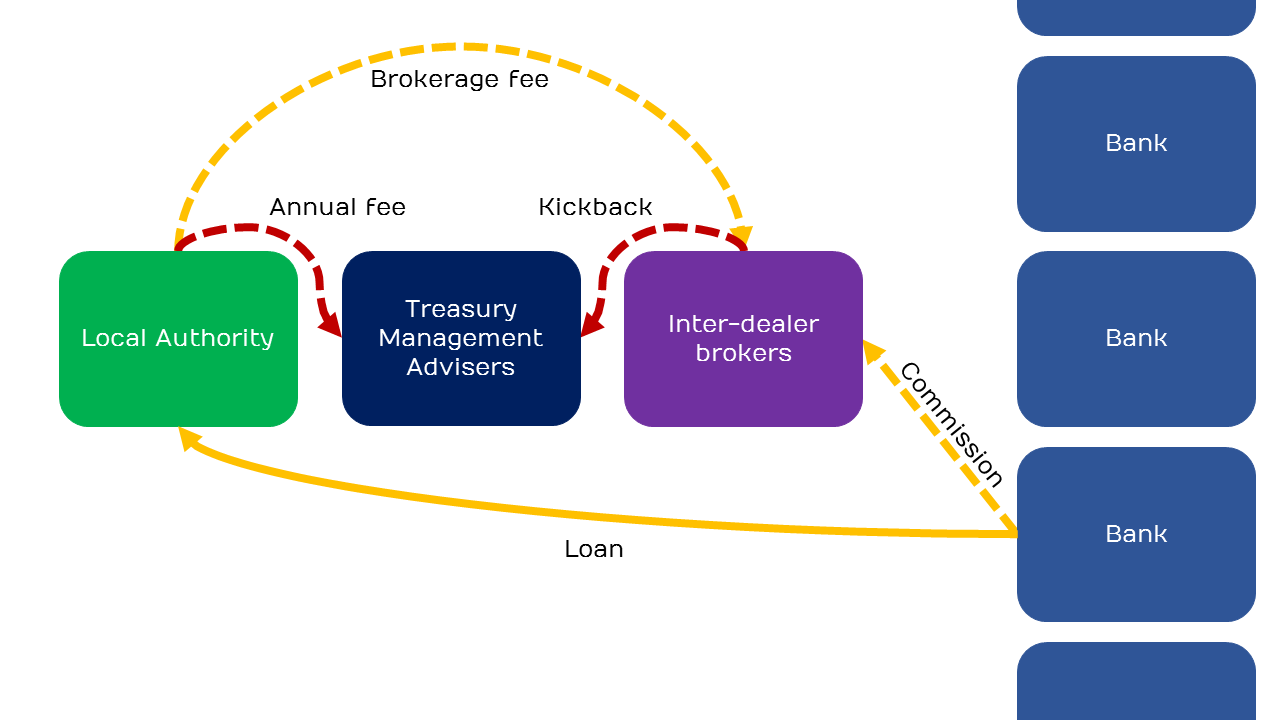

In the previous posts in this series, 5 reasons LOBO loans to local councils are a rip-off, Part 1 and Part 2, we saw how these long-term loans to councils, from banks, are a lose-lose bet for councils. We also saw how they suck taxpayer money out of the public sector into the pockets of bankers and how, due to the role of interdealer brokers, they’re more expensive to arrange than equivalent loans from central government.

In this post I’ll give another two reasons why LOBO loans are a rip-off: they’re pushed by advisers who get a kickback for arranging them; and they’re ignored by ‘independent’ auditors whose biggest clients are the banks who peddle LOBOs.

4. LOBO loans are recommended by advisers who get a kickback for arranging them

In the last post I mentioned a curious breed of public sector consultants called Treasury Management Advisors. These are private firms hired by local councils to advise their treasury teams on how best to arrange the council’s finances e.g. where to invest spare cash and where to borrow the money required for large capital projects.

These firms are generally hired on contracts which run for several years and are paid an annual fee for their advice. At the end of the contract the council puts a out a request for new firms to tender for the job. Typical of such requests was one put out by Camden Borough Council in 2012, which DRUK asked for via a Freedom of Information request.

In the request for quotations the council clearly specifies the service it expects from the Treasury Management Advisers (here called Treasury Management Consultants) in relation to borrowing.

“The Council considers that in all circumstances that the contractor act in the best financial interests of the Council and offers guidance when required.”

“The contractor will offer advice on appropriate borrowing, including acceptable levels of borrowing, rates and terms, having regard to our financial position.”

In summary, the Treasury Management Consultants are expected to provide advice on council borrowing that is in the best interests of the council. So how come so many councils that have employed these firms have ended up with large amounts of debt owed to private banks in the form of LOBO loans, which, you’ll remember from the first post, are a lose-lose bet for councils?

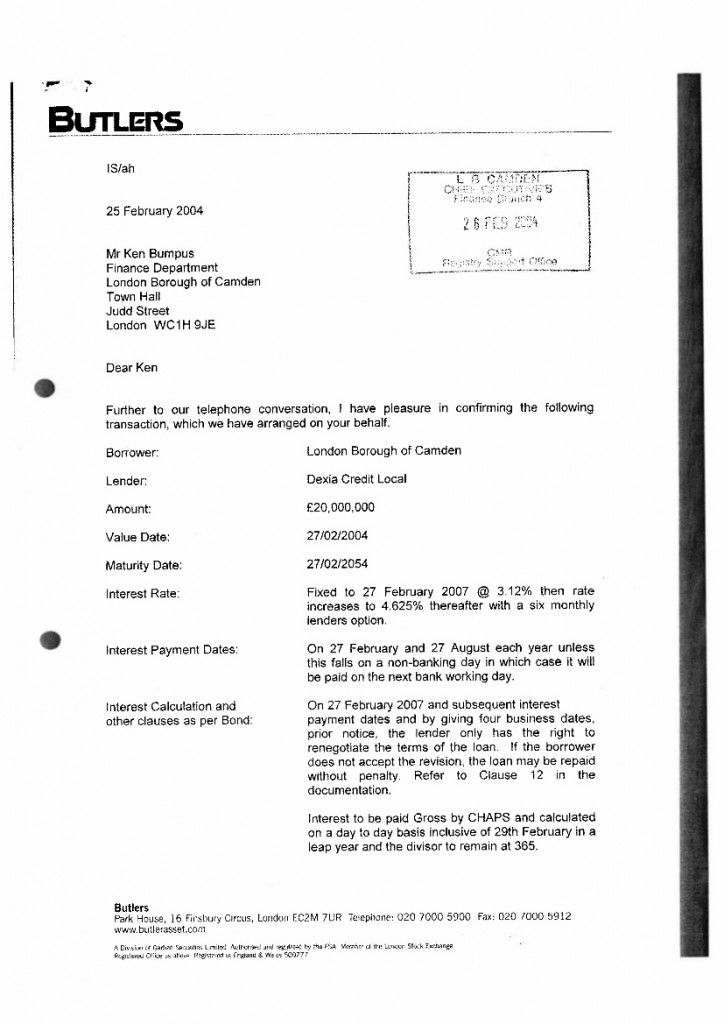

Could it be that the Treasury Management Advisers are not, in fact, operating in the best interests of councils at all, but rather in their own best interests? To answer this question we need to look at another Freedom of Information response from Camden Borough Council in which they released the paperwork related to a LOBO loan arranged in 2004. (Credit to Ranjan Kumaran for this FoI.)

The paperwork includes a letter from Butlers – Camden’s Treasury Management Advisers at the time – in which Butlers set out the details of the LOBO loan transaction which they “have arranged on [Camden’s] behalf”.

If you ignore the terrible value which LOBO loans represent for councils then the letter seems pretty innocuous. After all, Butlers are Camden’s treasury advisers – presumably it was their job to arrange loans on Camden’s behalf.

The situation gets murkier though when you look at the footer of the letter where it’s revealed that Butlers was, at the time, a division of Garban Securities Limited, itself a division of ICAP. Cast your mind back to the last post and you’ll remember that ICAP is one of the large interdealer brokers that earns huge commissions from banks, and large fees from councils, for setting up LOBO loan deals.

So here we have one part of a company providing advice on borrowing to Camden Borough Council, arranging a £20 million LOBO loan from Dexia on their behalf, while another part of the same company collects a huge fee for brokering the trade (confirmed in the same Freedom of Information request where it clearly states that Garban was the broker in this deal).

Are we really expected to believe that by providing this advice Butlers was acting in the “best financial interests of the Council”?

But surely this is just an aberration? This kind of thing didn’t happen on a regular basis, did it?

Apparently so. When local authorities looked to have lost over a billion pounds when Iceland’s banks collapsed in 2008 parliament’s Communities and Local Government Committee held an inquiry to find out what had happened. The relationship between Treasury Management Advisors and interdealer brokers was at the centre of the story:

“The evidence which we have examined has raised concerns about potential conflicts of interest and questions as to whether there are any financial transactions between treasury management advisers and brokers that might compromise the independence of advice being given to local authorities. There is a strong case for a full investigation by the FSA of the services provided by local authority treasury management advisers. We recommend that such an investigation be carried out as soon as possible.”

Alas, no such investigation was forthcoming from the UK’s notoriously slumbersome financial regulators.

It’s not just Butlers whose conduct is in question either: Sector Treasury Services – a company which provides Treasury Management Advice to a large number of local authorities – acquired Butlers from ICAP in 2011. In its review of the merger the Competition Commission noted that a part of Sector’s income came from

“a share of the brokerage fees earned by the money broker Tullet Prebon, paid to STS if an STS client elects to transact through Tullet Prebon in relation to the arrangement of Lender’s Option Borrower’s Option (LOBO) loans.”

Sector is now known as CAPITA Asset Services, reflecting the fact that it’s a part of the huge outsourcing company notorious for its role in PFI deals. Another DRUK Freedom of Information request has revealed that Sector typically earned 0.066% of the face value of a LOBO loan as a kickback whenever the deal was arranged through Tullett Prebon or ICAP.

In the context of a single LOBO loan of £20 million like the one we saw earlier, that would mean a kickback from Tullett Prebon to Sector of about £13,200. Hardly peanuts.

Is it even possible to imagine that these kickbacks had no influence on the borrowing advice provided to Councils by these firms? And if not, what does that mean for the legitimacy of the LOBO loans that were arranged under these conflicts of interest? Should struggling councils be expected to honour these dubiously-arranged deals which represent terrible value for the taxpayer?

5. LOBO loans are ignored by ‘independent’ auditors whose biggest clients are the banks peddling LOBO loans

As we saw in the first post it hasn’t been easy convincing Councils that they’ve been the victims of an elaborate scam perpetrated by banks, brokers and treasury advice firms. Chief finance officers at local authorities have been very resistant to the arguments of experts like Abhishek Sachdev and Rob Carver who’ve set out in great detail, and in front of a parliamentary inquiry, why LOBO loans are a lose-lose best for Councils.

One of the reasons Councils have been so bullish in their defence of LOBO loans – an argument that DRUK has frequently encountered when trying to obtain LOBO contracts via Freedom of Information requests – is that their accounts are audited each year by independent accountants. If LOBOs really were a big stain on Council balance sheets then surely the auditors would have picked up on it?

For example, in refusing to disclose the contracts for £98m of LOBO loans, Swansea Council said

“Whilst you maintain that there is a public interest in releasing this information because the Authority can only be held accountable for its borrowing decisions by making this information publicly available, I can confirm that scrutiny of the Authority’s borrowing decisions is conducted by external, independent auditors on an annual basis.”

Swansea Council publishes its Annual Statement of Accounts on its website, as do most Councils. Currently you can view the accounts as far back as 2006-07. In every year between then and now the appointed external auditor for Swansea Council is PricewaterhouseCoopers.

PwC is one of the ‘big four’ accountancy firms, along with Ernst & Young, Deloitte and KPMG. When they’re not rubber stamping the accounts of the City and County of Swansea you’ll find PwC auditing all kinds of illustrious clients in the world of big business. Barclays Bank, whom, until 2015, PwC have audited for 120 years are just one of those illustrious clients.

Five of Swansea’s LOBO loans were taken out with Barclays.

Auditing a major bank is a huge account for PwC; auditing a local authority is not. So if the expediency of sheer incompetence wasn’t reason enough in itself to quickly skim over the LOBO loans in Swansea Council’s accounts without so much as a second glance, perhaps that fact would be.

Posted in Blog