Introduction

Public debt audits are a tool used successfully to challenge the legitimacy of public debt, most notably in the global south. Debt audits are being increasingly adopted in EU economies as the 2008 financial crisis resulted in a significant increase of indebtedness throughout developed western economies.

Debt audits are typically undertaken either at the central government level, as an expert led, top-down investigation of Government debt, or at the local level with bottom-up action by citizens to audit local authority and municipal debts.

Some countries, such as France, have attempted a fusion of the two approaches.

In an era of financialisation, with a myriad of increasingly complex financial instruments bombarding consumers, expecting the general population to possess a systems based understanding of how our economy functions, the way public authorities are financed and how the financial sector actually works is increasingly unrealistic.

Hidden behind an exclusive pay wall of elitist financial sector jargon, the public are bamboozled by talk of ‘fiscal charters’ by politicians, falsely equating the nations finances with that of the household.

Meanwhile, public sector indebtedness (resulting from failure in the banking system) is used as cover to implement unpopular austerity policies, which transfer bank debts to the state and onto individuals.

Within this framework, if it were shown that public debts were somehow illegitimate, that citizens had a right to demand a moratorium on repayments – or even the cancellation of part of these debts – the political implications would be enormous.

Financialisation of the economy in the neoliberal era has coincided with the depoliticisation of public finance, as decisions regarding the day-to-day financial management of our economy are quietly removed from the political sphere, and transferred to the realm of unelected technocrats and financial elites.

EU nations joining the European currency have effectively ceded financial sovereignty and monetary policy to a cabal of unelected technocrats at the European Central Bank (ECB) and European Commission (EC) level.

Nowhere has this process become more apparent than in the political struggle played out on the global stage between ECB and EU bureaucrats, and the elected officials and citizens of Greece, regarding proposals to address the realities of the Troika’s Greek bailout program, and to restructure unsustainable Greek debt.

Within a political context where the power of elected politicians to question the financial terms of how our economies are run, and whose interests are being served has been eroded, debt audits are a powerful tool to mobilise and educate the public, and to politicise financialisation as the root cause of indebtedness.

Debt audits provide an important tool to educate and mobilise citizens to demand a more transparent and accountable financial system and to embolden elected representatives to act in the public interest against powerful financial institutions.

Why Audit European Public Debt?

Once viewed as tool employed by emerging economies in the global south, most notably Ecuador, debt audits have grown in popularity in recent years, as the global financial crisis of 2008 has brought surging public debt levels to US and EU economies – and with it, growing global awareness of the extent to which finance exerts control over every aspect of our lives.

Rarely mentioned in mainstream discourse, debt audits are actually an institutional duty of the state, set out in European law. Albeit a duty not exercised by EU members.

EU regulation No. 472/2013 requires EU member states subject to a macro-economic adjustment program (including Greece, Ireland, Portugal) to “carry out a comprehensive audit of its public finances in order to assess the reasons that led to build up of excessive levels of debt, as well as to track any irregularity”

Additionally, The United Nations Guiding Principles on Foreign Debt and Human Rights (A/HRC/20/23) adopted by the UN Human Rights Council in July 2012 calls upon states to carry out periodic audits of their public debt in order to ensure transparency and accountability in the management of their resources, and to inform future borrowing decisions.

Ecuador Debt Commission

In Ecuador in 2008 President Rafael Correa, an economist who had threatened to default on the countries debt since his election in 2006, established a debt audit commission in order to formally challenge the nations finances.

The commission, chaired by Ricardo Patino, established that growth in Ecuador’s debt over the past three decades had “occurred for the benefit of the financial sector and transnational companies and clearly went against the interests of the country.”

The commission set out in a 172-page report that global bonds due in 2012 and 2030 “show serious signs of illegality,” including “issuance without government authorization.“

The commissions report argued much of the debt was illegal, because ‘usurious’ rates of interest were charged. Some bonds were issued without proper government

authority; whilst other bonds were not registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States.

The report also suggested the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate increases in the late 1970s amounted to a “unilateral raising” of global interest rates.

Whilst Ecuador’s Debt Commission made no specific recommendations regarding solutions to the debt crisis, its analysis provided President Correa a solid economic and political base from which to pursue a policy of sovereign debt default.

Correa’s favoured policy was extensively sign-posted to markets since his election 2006, according to David Bessey, who manages an $8billion portfolio of emerging market debt: “Correa’s been pretty vocal about looking for reasons to not pay the debt”

In December 2008, Rafael Correa made good on his word that he ‘will not sacrifice spending on health and education to pay the debt’ by ceasing payment to Ecuador’s bond holders, stating:

At the time of Ecuador’s debt default; foreign obligations amounted to 21 per cent of the nations $44 billion gross domestic product.

The timing of Ecuador’s default, in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis allowed sufficient breathing space to engineer the repurchase of Ecuador’s Government debt, via Bunco Pacifico, just as the price of its Government bonds collapsed to between 35 and 20 cents in the dollar.

According to Reuters, the levels at which Banco Pacifico repurchased Ecuadorian debt was “just high enough that vultures [vulture funds] didn’t want to amass a large position, and ensured that any future restructuring would face little organized opposition just because Ecuador’s bondholders were so fragmented.”

Whist it should be noted that Ecuador is tiny, amounting to just 0.5% of the emerging market index, the success of its default cannot be ignored.

Effectively, Ecuador pulled off a stunning debt restructuring coup on the back of a national debt audit and popular mandate for default, described as “probably the most successful and least fraught debt restructuring in the history of Latin American sovereign defaults.”

Citizen-led PACD Public Debt Audits in Spain

In Spain, citizen’s action has focused upon municipal resources. After the inspiring assemblies of the squares in 2011 (known as 15M), hundreds of autonomous groups were set up to develop localised issue specific campaigns.

The Platform for a Citizen Debt Audit (PACD) is one of these local initiatives with a local focus, and a growing national network of members.

The PACD formed in late 2011, with the aim to mobilise citizens around financial transparency and accountability of institutions, and to demand the repudiation of debts that citizens deem to be illegitimate.

Since 2000 the debt of local councils in Spain has more than doubled, impacting directly upon the essential services local authorities are meant to provide. The PACD proposes the use of Citizen Debt Audits as an instrument for the Spanish population to critically analyse the debt policy carried out by the authorities and its impact on the population.

The PACD describes a Citizen Audit as “a process to, collectively, understand how we have arrived at the current situation; what economic, social, cultural, environmental, gender and political impacts has this indebtedness created.”

PACD helped set up Citizens Municipal Observatories (CMOs) across Spain. CMOs are initiatives consisting of groups of people locally organised who provide clear information about municipal budgets through an online platform (OCAX) and workshops, which support citizens with inquiries to the municipality.

Thanks to the combined work of the PACD and the local CMOs, numerous municipalities have passed motions against illegitimate debt, “marking an important victory in introducing the concept of illegitimate debt into the field of institutional politics.” In Madrid and Barcelona, the recently elected mayors supported by the social movements have announced that they will set up official audit commissions for their municipal debt.

Eric Toussaint and David Millet wrote about citizen led debt audits in The Occupied Times where they state:

“Carrying out a citizens’ audit of public debt combined with a strong popular movement for suspension of repayments should culminate in the abolition or repudiation of the illegitimate part of the public debt and in a drastic reduction of the remaining debt. […] The fact that governments continually blitz the media with rhetoric about transparency but oppose citizens’ audits is an indication of the sorry state of our democracies. Real transparency is the ruling classes’ worst nightmare.”

The PACD are currently expanding citizen audits from municipalities into other areas of state spending, such as healthcare, and now enjoy the support of several progressive Mayor’s including Barcelona’s Ada Colau, who have emerged from the social housing and debt audit social movements to run municipal authorities.

France – Committee For A Citizens Audit Of The Public Debt.

In 2014, the Committee For A Citizen’s Audit On The Public Debt issued a 30-page report on the state of French public debt, its origins and growth in recent decades.

The report was generated by a group of experts in public finances under the coordination of Michel Husson, one of France’s most prominent critical economists.

However the origins of the report lie within a broad network of local audit groups under the Audit Citoyen banner, mobilising thousands of people behind local debt audits, and building public momentum behind the national scale audit report and the politicising the case for cancellation of illegitimate debt.

The neoliberal argument in favour of austerity policies claims that Government debt is due to unreasonable public spending levels; that societies in general, and the lower classes in particular – maintained by the welfare state have grown accustomed to ‘living above their means.’

This is nonsense. In the 30 years from 1978 to 2012, French public spending as a percentage of GDP has actually decreased by two percentage points.

What Explains Rising French Public Debt?

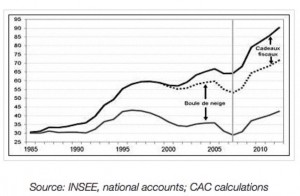

The report on French debt draws several important conclusions. Primarily, that the rise in the state’s debt in the past decades cannot be explained by an increase in public welfare spending.

Audit Citoyen’s report concludes some 59% of French public debt is considered illegitimate, arising from corporate ‘tax breaks and excessive interest rates.’

Firstly, the debt is caused by a fall in the tax revenues collected by the state. Massive tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations have been carried out since 1980 shifting the burden of tax onto the shoulders of the working poor.

Firstly, the debt is caused by a fall in the tax revenues collected by the state. Massive tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations have been carried out since 1980 shifting the burden of tax onto the shoulders of the working poor.

In line with the neoliberal mantra, the purpose of these tax rate reductions was to allow for investment and to generate employment.

Instead, French tax revenues have decreased by approximately five points of GDP, whilst unemployment, particularly in the youth bracket, remains stubbornly high.

The other major contributing factor cited by the Audit Citoyen Report is the increase in interest rates, especially in the 1990s. Interest-rates hikes favour creditors and speculators, to the detriment of debtors.

Instead of borrowing on financial markets from banks at prohibitive interest rates, had the French state financed itself by issuing bonds and borrowing at historically normal rates, the public debt would be lower than present current levels by 29 GDP points.

This is known as the debt “snowball” effect, as more and more of the states resources are required to fund interest repayments, not fund public services.

Whilst the French debt audit has not resulted in political solutions to the debt problem at the national level, it has served to educate and mobilise French citizens and further politicise the real causes of the French public debt situation.

Greece: Truth Committee on Public Debt

In Greece in January 2015, the election of left-wing Syriza Government on a clear anti-austerity platform created the political impetus for a critical examination of Greek debt, which was generated through irresponsible bank lending in the run-up to the 2008 crisis, and in the transfer of private bank debt to the Greek state via successive memoranda agreements from 2010-15 via the Troika of the European Central Bank (ECB), European Commission (EC) and International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The memoranda agreements extended additional loans of around 300 billion euro to Greece, in exchange for compliance with a ‘structural adjustment’ program designed to drastically shrink the state, and slash welfare costs.

The Public Debt Truth Committee was established by Syriza speaker of the house Zoe Konstantoupolou, and included a mixture of Greek and EU academics, and debt audit experts including Eric Toussain (of Belgium’s CADTM).

The Debt Truth Committee was given a mandate to identify “the historical, financial and other processes relating to the accumulation of debt” and to determine “what part of the debt can be defined as illegitimate, odious, or unsustainable.”

The Public Debt Truth Committee produced its landmark report in June 2015 after an intensive review of official Government records and loan contracts.

As with the findings of the French report, the Public Debt Truth Committee found that “rather than being the result of high public deficits, the increase in debt was related to the growth in interest payments.”

Furthermore, the Committee found Greek “public expenditure to be lower than any other Eurozone member”, and discovered “the only item of public spending higher as ratio of GDP was defence – the subject of ongoing corruption scandals.”

The Committee found the terms of the Greek ‘bailout’ and austerity package implemented by the Troika breached fundamental human rights.

Lenders knew unequivocally that by enforcing the terms of the loans and resulting restructuring program, the Greek state would be unable to meet its future repayment commitments, the extent of the ‘contractionary effect on output’ would be severe and the human suffering imposed by the program would be immense.

A report by Jubilee Debt Campaign concluded 90% of the so-called Greek bailout loans had gone to repay reckless European banks, not to benefit Greek citizens.

Debt was considered odious by the Committee if the effect of the loan was unconscionable and its effect would deny people their fundamental civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights.

Elements of the debt were declared to be illegal, if the creditors (e.g. hedge funds) acted in bad faith (such as with the sale of credit default swaps) or foreign banks which violated domestic contract laws through not obtaining project approval prior to extending loans.

Debt owed to private creditors was deemed illegitimate if: “the terms and conditions attached to the loans were grossly unfair, unreasonable, unconscionable or otherwise objectionable.”

Greece’s Government debt to GDP ratio has gone from 133% in 2010 to over 175% today.

Less than 10% of the so-called bailout money has actually reached the people who need it, and as it stands today, every new baby born in Greece is born owing €41,000.

Isolated politically, and faced with unrelenting political pressure from the ECB and EC, the Syriza Government failed to turn the political momentum created by the Public Debt Truth Committee report and historic 61% “Oxi” referendum vote against further EU led austerity into default and restructuring of Greek public debt.

Towards UK Public Debt Audits

Following a recent visit to Greece with the Greek Solidarity Campaign, Green Party MP Caroline Lucas wrote in the Huffington Post of the need for a similar process for

dealing with problem UK debt to that pursued by the Greek Public Debt Truth Committee.

The UK, a creditor nation with an over-sized financial sector four times annual GDP output has a distinctly laissez-faire attitude to high levels of indebtedness. Mounting global debt from which the City of London ultimately profits.

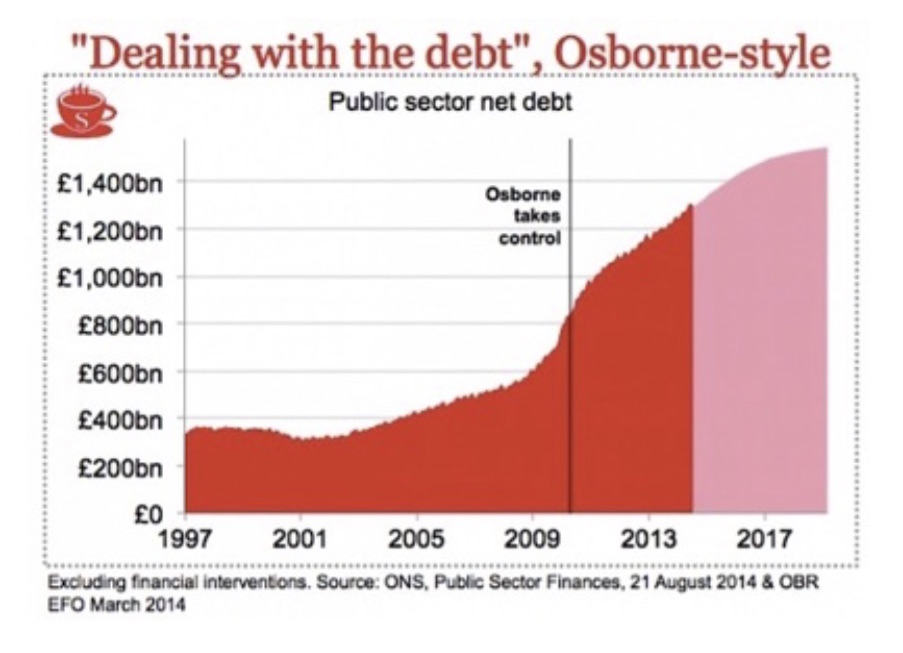

UK public debt levels have exploded since George Osborne became chancellor in 2010, despite austerity policies sold on the basis of reducing UK debt.

One of George Osborne’s first acts as Chancellor was to increase the lending margin on loans to local government via the Public Works Loan Board, increasing the margin from 0.15% to 1%, hiking Government lending costs to local authorities by 25% overnight and encouraging borrowing from banks.

Current Bank of England Governor Mark Carney openly speaks of increasing the size of the UK financial services sector to between twelve and fifteen times UK GDP by 2050, from around four times GDP today.

Greece meanwhile, having suffered 5 years of brutal austerity at the hands of its EU creditors is more open to critically reviewing the responsibilities of creditor vs debtor nations and exploring the options for sovereign debt restructuring.

The causes of public sector accumulation of debt in the UK are slightly different to those in Greece, but many of the drivers are the same.

Tax avoidance by UK corporates and rich ‘non-domiciled’ elites continues to deprive HMRC of tax receipts amounting to a loss of at least £34billion per year, with little

fear of prosecution for offenders, despite widespread public outrage following the HSBC ‘Swiss Leaks’ tax scandal.

Borrowing at high interest rates from private banks is widespread throughout the UK public sector, even if such borrowing is not necessitated by the lack of available central bank financing, as in Eurozone nations like Greece.

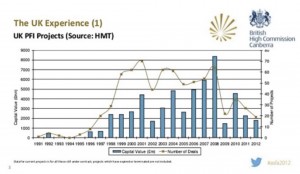

Bank financed Private Finance Initiative (PFI) infrastructure projects, which are most concentrated in the NHS, have amassed around £310 billion of off-balance-sheet infrastructure obligations for UK taxpayers since 1991.

A figure more than four times the budget deficit used to justify austerity cuts to government budgets and local services.

A 2011 Treasury Select Committee Report on PFI financing found that the interest rates payable on PFI contracts were at least 3-4% above the cost of Government debt. James Wardlaw, a banker with Goldman Sachs noted the costs of PFI financing had risen considerably since the 2008 crash: “In terms of the cost of that finance, it is definitely higher […] the levels were 60 [basis points] over swaps at the peak, and now we are talking 250 and more.”

Despite PFI being shown to be a complete rip-off for taxpayers in the UK, the PFI/ PPP model is currently being exported globally, including the Attika schools project in bankrupt Greece, and London conferences promoting Africa PPP’s.

Housing Associations, another form of off-balance-sheet financial vehicle have amassed somewhere in the order of £60-135 billion in debt and financial liabilities, borrowing from banks and bond markets since Margaret Thatcher privatised social housing construction and stopped councils building new houses in the 1980’s.

Off-balance-sheet financial vehicle debt is ripe for public scrutiny, yet because public sector finance is unregulated, and Housing Associations and PFI debts are considered

off-balance-sheet, they have never been seriously reviewed or audited by public authorities or the general public.

Housing associations were considered ‘private entities’ until a reclassification of their assets as “public sector” in October 2015 by the ONS, and are expressly excluded from FOI legislation.

Who Is Campaigning For Debt Audits In the UK?

Campaign group Positive Money have successfully politicised the issue of the privatisation of the UK money supply by private banks, forcing the Bank of England to acknowledge 97% of the money supply is created by banks when banks issue loans.

Yet groups like Positive Money lack the required mass grassroots support and political leverage to legislate for structural reform of financial markets in the UK, where financial services is the largest and most powerful political lobby group.

Very few charitable grant funders are prepared to fund work targeting UK debt, with NGO’s like Jubilee Debt Campaign focussed primarily on foreign debt issues, including third world debt, and EU peripheral countries including Greece.

It is important to note that a popular UK debt audit would represent a serious challenge to the profitability and political prestige of the City of London, with financial services a leading ‘growth’ engine of the UK economy.

To be successful, in the absence of political will to challenge the City, a combination of the debt audit tactics employed by Spain, Greece and France would be necessary, to educate citizens, politicise issues of indebtedness through local audits, to and to create the necessary media space and political leverage to pursue national policy solutions.

What is currently lacking in the UK however, is both the funding and the NGO/ campaigning and political architecture to support debt audit work at both the national and local level.

Several small campaign organisations are already attempting to audit UK municipal debt, with the most advanced, Debt Resistance UK undertaking a local authority debt audit, sparking a DCLG inquiry into local government bank loans.

The People vs PFI are examining PFI contracts in the NHS with the objective of forcing PFI contract renegotiation and debt reduction and/or the buyout of PFI debt, alongside abandoning PFI as the UK infrastructure model of choice.

Both organisations are currently reliant upon the use FOIA requests as a research tool to access financial contracts not otherwise available in the public realm.

The introduction of application fees for FOIA requests, widely expected under FOIA reforms would effectively place public interest financial information and scrutiny out of reach of most UK citizen campaigners.

Plan B for Europe. A Pan-European Debt Audit Movement?

A further opportunity for the pursuit of UK debt audits may be presented by the 2017 EU referendum on the future of the UK’s role within Europe.

A new EU wide initiative labelled ‘Plan B for Europe’ has been proposed by Jean-Luc Melanchon, Yanis Varoufakis, and Zoe Konstantopolou following the bitter experience of Syriza’s confrontation with the EU and ECB.

The idea is to agree a common set of progressive economic policies within left-wing Eurozone parties, so resurgent anti-austerity movements in Portugal, Spain, Greece, and the UK can develop a shared understanding with their allies – presenting a more powerful and unified voice during EU negotiations.

Plan B for Europe is calling for European wide public debt audits to critically examine the basis for austerity and restructuring programs within struggling Eurozone economies, extending to a conversation around currencies and trade.

The existence of EU and UN regulations obliging Governments to perform period debt audits and to critically examine the causes of problem debt lends the proposals a sense of practical legitimacy and provides an entry point for political discussion on debt audits in the UK.

Conclusion

Debt audits are a powerful tool to challenge and politicise indebtedness, identifying structural causes of public debt including tax avoidance and borrowing at high interest rates, whilst critiquing and undermining the political construct of austerity.

Debt audits appear to work best when paired at the local and national level, educating citizens and empowering politicians with a strong political mandate for confrontations with the nations creditors.

Unilateral debt defaults were successful in Ecuador. Yet the set of factors which led to a successful default (small economy, mid-financial crisis, broad political mandate for default) will prove difficult to replicate for larger Eurozone economies generally, and creditor nations such as Britain and France specifically.

Rather, creditor nations within the EU such as Britain should concentrate on building grass roots capacity to conduct local debt audits, complimented by the development of the skills and capacity required for a national debt audit project.

Scope for political co-operation with fellow EU economies to ensure debt audit obligations under EU and UN regulations are met provides opportunities to fund and coordinate civil society debt audit projects at the European level, whilst politicising the causes of public debt within the UK ahead of the looming EU referendum.

Posted in Blog